research

some of my research interests

Hot Jupiter Demographics

Hot Jupiters – giant planets that orbit their stars in less than ten days – were the first exoplanets to be found. Today, we know of hundreds of them, and some individual planets have been studied in great detail, including atmospheric characterization by JWST (e.g. WASP-39b). The discovery of such large planets so close in to their stars came as a surprise to astronomers, and three decades later, we still do not have a good idea of how they formed.

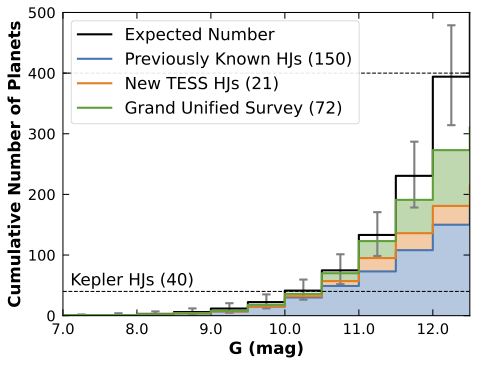

Most of the currently known hot Jupiters were discovered by various ground-based surveys, such as HAT and WASP. Each of these surveys had different selection criteria and biases, which has made combining their discoveries into a single sample difficult. Hot Jupiters are also relatively rare, occurring around only 1% or less of Sun-like stars. This meant that NASA’s Kepler mission discovered only 40 such planets. As a result, it has been challenging to study hot Jupiters as a population.

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) mission is searching stars across the entire sky for planets. This means that it will “re-discover” all of the previously known hot Jupiters as well as find new ones. We now have the opportunity to create a homogeneous sample of hot Jupiters to study their demographics. I forecast that we would be able to create a sample of 400 hot Jupiters by searching stars brighter than G < 12.5 mag (Yee, Winn & Hartman (2021)).

For my PhD thesis, I have been conducting the TESS Grand Unified Hot Jupiter Survey in order to confirm and characterize the new hot Jupiter candidates discovered by TESS and thereby create this demographic sample. I work with members of the TESS Follow-up Observing Program to obtain photometric, spectroscopic and imaging observations to rule out false positives. I then use high-precision spectrographs including Keck/HIRES, Magellan/PFS, and WIYN/NEID to measure the masses of these planets.

Over the past year and a half, I have observed more than 150 planet candidates from TESS, of which at least 70 have turned out to be real planets, with the first 30 published in Yee et al. (2022a), Yee et al. (2022b). In collaboration with other members of the community, we expect to complete our survey in 2023 and have assembled the largest ever statistical sample of hot Jupiters. Stay tuned for the demographic results that will arise from this work!

Dynamical Histories of Planetary Systems

Early astronomers saw our solar system as a clockwork mechanism – planets orbiting the sun, moons orbiting the planets, forever and unchanging. But we have since learned that things are more complicated than that. In our Solar System, the orbits of the planets are thought to have migrated over long distances, while our own moon is thought to have formed as a result of a giant impact between a Mars-sized object and the Earth. And as the Sun ages and turns into a red giant, the inner planets (including possibly the Earth), will eventually be engulfed. Our Solar System is a dynamic and sometimes violent place. What can we learn about the history of other planetary systems?

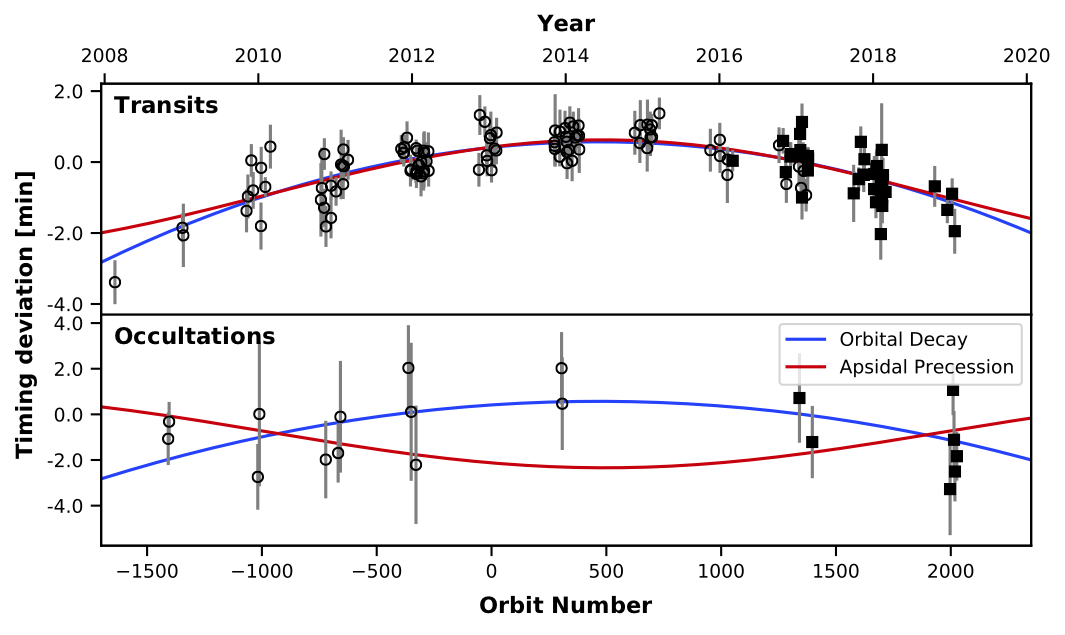

One fascinating planet I studied is the hot Jupiter WASP-12b. Building on a decade of data, particularly those compiled by Patra et al. (2017), and adding new observations from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, we found the decisive evidence showing that the orbit of this planet is decaying, and it will spiral into its star and be destroyed in just a few million years! See press coverage from Princeton and Popular Science for more details.

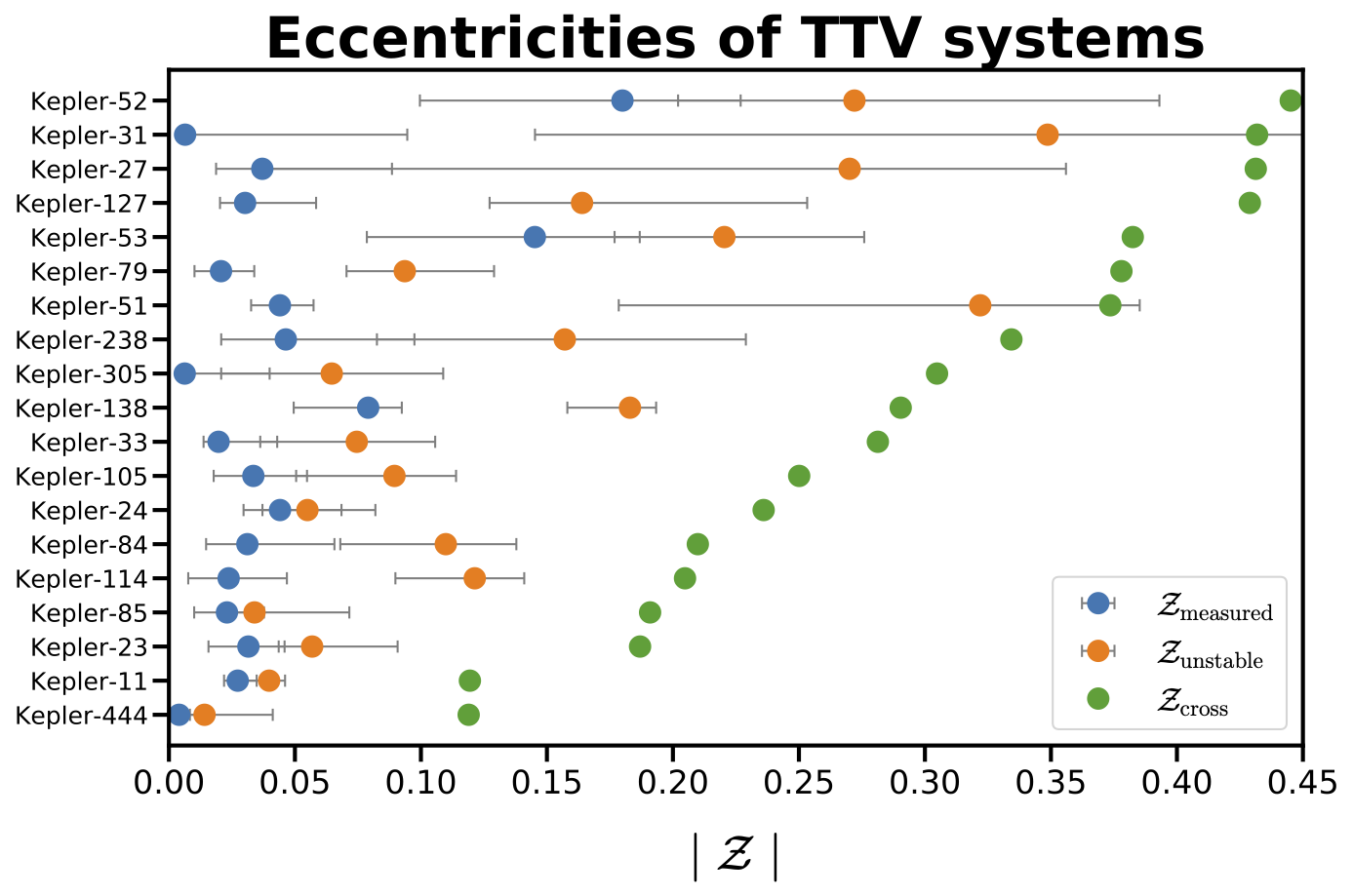

Apart from hot Jupiters, another type of planetary system we have discovered that are quite different from our own contain many planets on relatively short, tightly-packed orbits. Typically, these planets are slightly bigger than the Earth (we call them super-Earths and sub-Neptunes), and a planetary system may have three or more such planets all orbiting closer to their star than the Earth is to the Sun. One hypothesis that had been put forward is that these systems may have been sculpted by constant gravitational interactions leading to chaos and instability. Working with Dan Tamayo and Sam Hadden, we showed that this cannot have been the only process at work, and some dissipiation must have taken place to reduce these planets’ eccentricities and inclinations (Yee et al. (2021a)).

Stellar Characterization

Our methods for detecting and characterizing exoplanets depend heavily on a detailed understanding of their host stars. For instance, the transit detection method measures the tiny dip in a star’s brightness as a planet passes in front of it, with the size of this dip depending on the ratio of the planet’s to star’s radius.

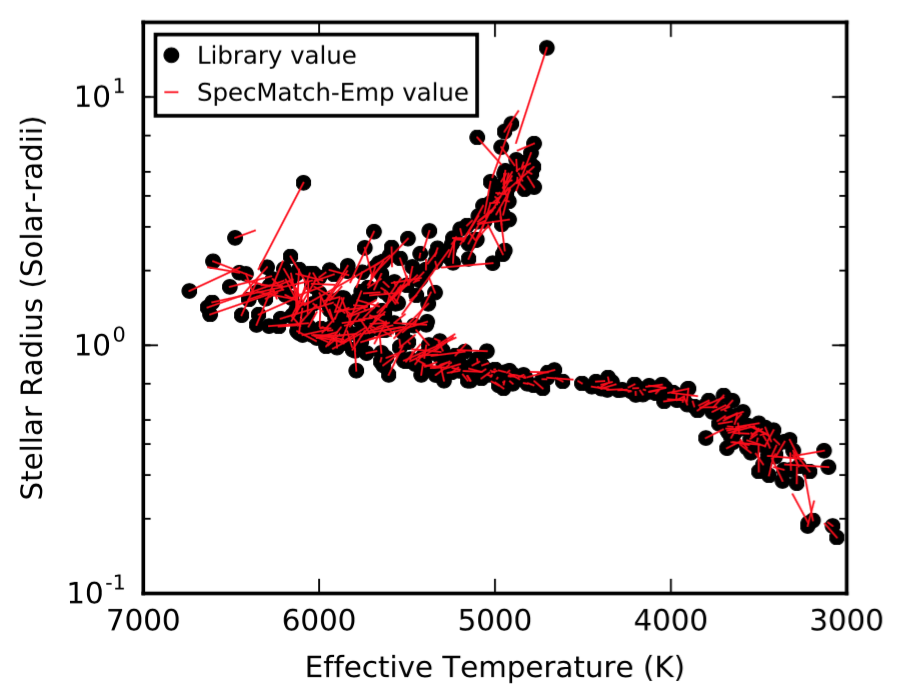

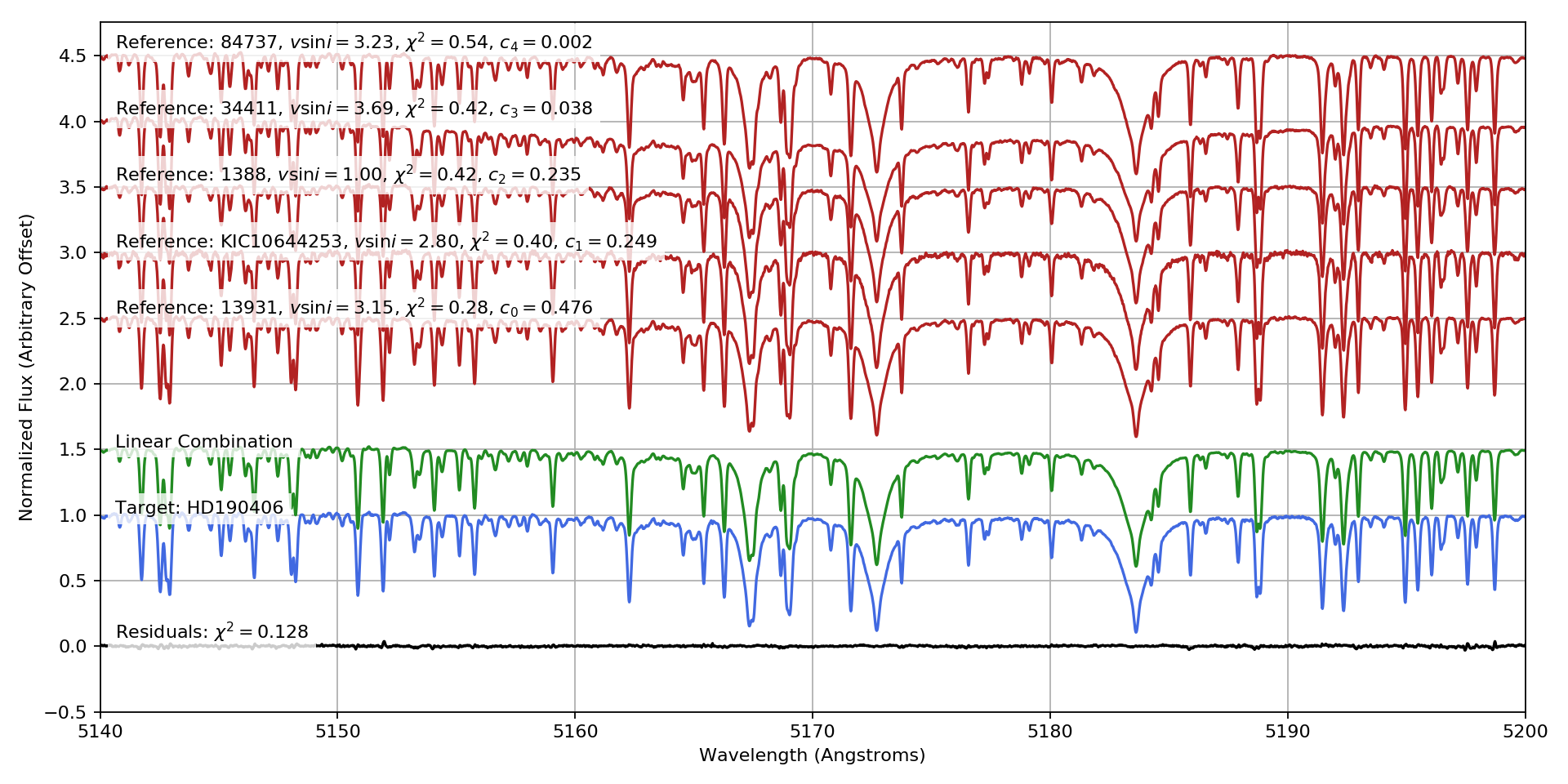

Working with Erik Petigura, I developed SpecMatch-Empirical, a new tool for characterizing the effective temperature, radius, and metallicity of a star from its spectrum. SpecMatch-Emp compares a target spectrum with a library of high resolution, high signal-to-noise observed spectra from stars with empirically-determined properties. Using empirical instead of synthetic spectra allows us to avoid model-dependent uncertainties particularly for late-type stars, and we achieve a precision of ~70 K in effective temperature and <10% in stellar radius.

SpecMatch-Emp has been applied to spectra from many spectrographs including Keck/HIRES, HARPS, and Coralie. More information can be found in Yee, Petigura and Von Braun (2017), as well as at the documentation page.

Planetary Obliquities

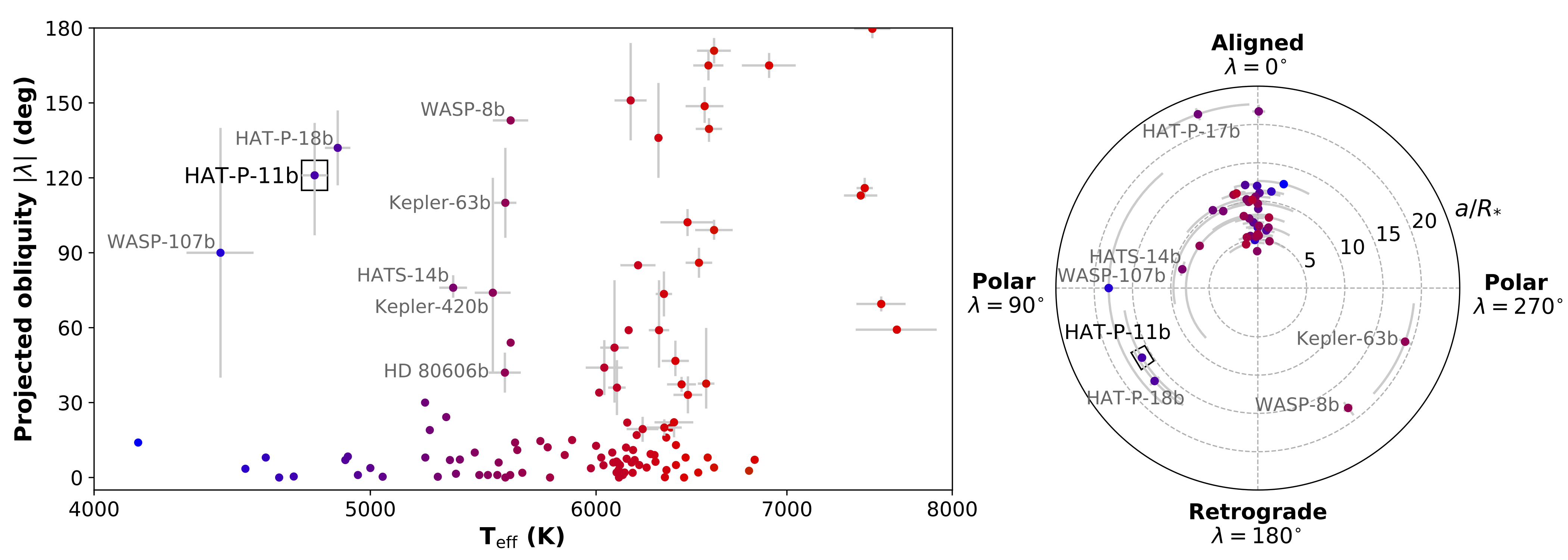

One of the major insights from the thousands of exoplanets we have discovered in the last two decades has been that exoplanetary systems often have very different architectures from our own Solar System. For example, HAT-P-11b - the first transiting hot Neptune discovered (Bakos et al. 2009), is on a highly inclined orbit that takes it over the poles of its host star. In contrast, the planets in our Solar System orbit in roughly the same plane, with their orbital axes aligned with the Sun’s spin axis to within six degrees. The large spin-orbit misalignment for HAT-P-11b is particularly unusual because it orbits a relatively cool star.

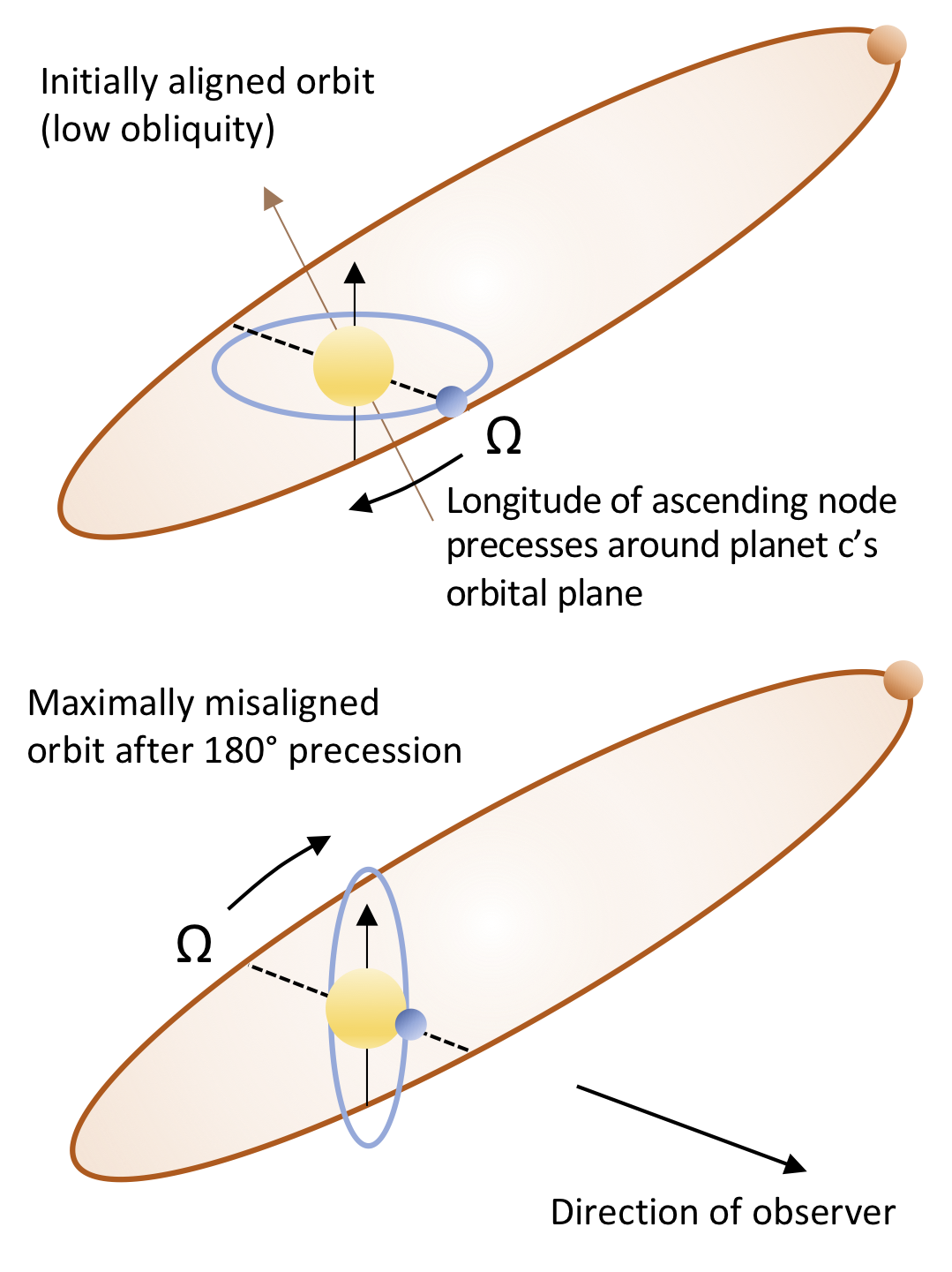

Using the decade-long radial velocity dataset for HAT-P-11 obtained by the California Planet Search team, I discovered a new planet, HAT-P-11c, orbiting with a period of ~ nine years. Together with Konstantin Batygin, we found that the presence of this outer planet could help explain the high inclination of the inner planet’s orbit by inducing nodal precession.

Understanding the origin of spin-orbit misalignments - whether they come from primordial misalignment of the protoplanetary disk, high-eccentricity migration, or dynamical interactions between planets - can in turn help us understand the formation pathways of close-in planets.